Categories

Categories

- Home

- Mining and Oil

- Mining

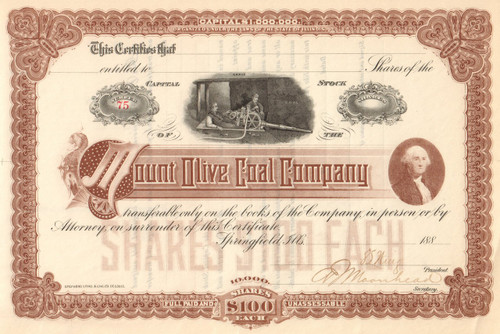

- Mount Olive Coal Company 1880's (Illinois)

Mount Olive Coal Company 1880's (Illinois)

Product Description

Mount Olive Coal Company stock certificate 1880's (Illinois)

Nice mining collectible. Great vignette of an underground mining scene with miners operating a drill. George Washington bust to the right. Unissued and not cancelled. Dated 188_.

Formed 1877 in Springfield IL, the company operated the Hoosier and Mount Olive mines in the Mount Olive township. it later beacme the Mt Olive and Staunton Coal Company.

As the tall grass prairie begins its gradual roll into the Ozarks, you will soon arrive in the small town of Mt. Olive. The land upon which the town now sits first belonged to a German emigrant named John C. Niemann, who bought forty acres in 1846. Soon more Germans came to the area and Niemann built the first store to service the many settlers. In 1868 a man by the name of Corbus J. Keiser purchased a half interest in the store, which was renamed Niemann & Keiser.

Afterwards, Kieser, along with a man named Mient Arkebauer, laid out a town plat on Niemann’s original forty acres. The name given to the town was Oelburg, which means "Mount of Olives.” In 1870 when the railroad came through, the settlement’s name changed once again to Drummond Station. A few years later in 1874, Neimann sold his interest in the store. It would be more than a decade that the town would finally settle upon the name Mt. Olive.

In the meantime, C.J. Keiser began to build an empire, opening the first coal shaft in 1875, establishing a milling business in 1876, and one of the first banks in 1882. Keiser was one of twelve original stockholders who owned the mine works. Coal mining in the area began to attract immigrants by the hundreds to work in the many mines.

While mining brought prosperity to southern Illinois, it also brought violence, property damage, and grief when turmoil began to rage between union activists and the mine owners. After miners had worked for years under dangerous and harsh conditions with very little pay, the first nationwide union, the United Mine Workers of America, was formed in 1890, to fight unfair wages and company stores. During this time, the mine companies totally controlled their workers’ lives, as they owned the mining towns and practically everything within them.

Though the next decade would see mostly defeat in the efforts to organize against the mining companies, activists continued to rally. Starting on July 15, 1892, in Mt. Olive, a bastion of union miners began to march south through one coal town after another, calling miners out of the pits. Holding impromptu rallies, they won much moral and material support from the communities and their residents.

Though gaining the support of the community members, they were not successful in recruiting many miners into the union, due to low wages and fear on the part of the miners. By the great strike of 1897, only about 400 out of 35,000 Illinois coal miners belonged to the United Mine Workers of America. However, the dedication of a few began to make a difference and by early 1898 an agreement was made between the union and management that workers would be restricted to an eight hour day, receive a mutually agreed upon wage, and company stores would be eliminated.

However, in the fall of 1898, the Chicago-Virden Coal Company, along with many others, sought to be exempted from the agreement. Failing in that effort, management proceeded to lock the union workers out of the mines and imported black strike breakers from the south. This, of course, provoked an immediate reaction among the union activists.

On October 12, 1898, the feared violence began at Virden, Illinois a small town some forty miles north of Mt. Olive. When the train carrying 180 black strike-breakers and their families, attempted to pass through a band of armed strikers, all hell broke lose as gunshots between the laborers and the armed guards broke out. In the melee, which became known as the Virden Massacre, seven miners and five guards were dead. Forty other miners, four guards, and the train’s engineer were wounded. The train was returned to St. Louis, with its cargo still aboard. Four of the miners killed were from Mt. Olive and were originally buried in the town cemetery.

Product descriptions and images

Please note that some pictures may only be representative of the inventory available. If we have more than one piece, we are unable to scan and display every piece. Unless otherwise noted, that there are variations for signatures, cancellation marks/holes, serial number, and dates. Colors will be as noted and pictured.

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...