Categories

Categories

- Home

- Food and Beverage

- Food Brands

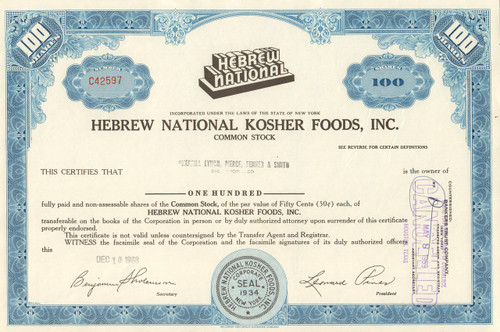

- Hebrew National Kosher Foods stock certificate 1960's (hot dogs)

Hebrew National Kosher Foods stock certificate 1960's (hot dogs)

Product Description

Hebrew National Kosher Foods stock certificate 1960's

Great vignette of the company's stylized name logo. Uncommon food brand cert from the famous hot dog maker. Great collectible and perfect novelty gift. Dated in the 1960's. Available in orange or blue borders.

The Hebrew National Kosher Sausage Factory, Inc., was founded on East Broadway, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1905. The company was founded by Theodore Krainin, who emigrated from Russia in the 1880s. By 1921, the factory was registered as government inspected establishment #552 by the United States Bureau of Animal Industry with Theodore Krainin as proprietor. Alfred W. McCann writing in a 1921 Globe and Commercial Advertiser article cited Hebrew National as having "higher standards than the law requires."

McCann wrote the article during a crusade for commercial food decency standards, in which the Globe was prominent. He wrote, "More power to Krainin and the decency he represents! Such evidence of the kind of citizenship which America should covet is not to be passed by lightly." Hebrew National "served the Jewish neighborhoods of immigrants from Eastern Europe and Germany and soon developed a favorable reputation among the other Jewish residents of New York City."

In 1934, after a bankruptcy action, the certificate of incorporation for Hebrew National Sausage Factory listed Solomon Levinson, Sylvia Marans and Miriam Spector, all of Brooklyn, as directors and shareholders. In 1937 after an increase in capital stock, Jacob Pinkowitz was listed as an officer. The company was bought by Jewish Romanian immigrant butcher Isadore Pines (born Pinkowitz). In 1935, Isadore's son, Leonard Pines, took over the business. In 1965, Hebrew National came up with the slogan that they've used ever since: We answer to a higher authority — a reference to Jewish dietary laws and a claim to higher quality that was able to appeal to both Jewish and non-Jewish markets. In 1968, the Pines family sold Hebrew National to Riviana Foods, which was taken over by Colgate-Palmolive in 1976. In 1980, Isidore "Skip" Pines, grandson of Isidore, bought the company from Colgate-Palmolive for a fraction of the price it was originally sold for.

The health food movement of the 1980s, with CEO Steve Silk at the helm, encouraged the company to stick to a recipe that used no artificial colors or flavors, and to minimize other potential modernizations of the recipe. This strategy ultimately proved successful, and with a growing revenue, Hebrew National hoped to transform itself into a large conglomerate through acquiring other brands, in order to compete with the food giants that dominated the industry.

Hebrew National developed a non-kosher brand called "National Deli". This strategy was less successful, and National Foods was acquired by ConAgra Foods in 1993. The National Deli brand was sold off in 2001 to a former Hebrew National employee, and still operates today out of Miami, Florida. The site of Hebrew National's manufacturing plant had been New York City for many years; it moved to Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1989. The Indianapolis plant was closed down in 2004 as operations were consolidated with the ConAgra Foods Armour hot dog plant in Quincy, Michigan.

Ironically, Hebrew National beef products cannot be eaten by many observant Jews, despite the fact that Hebrew National is probably one of the most well-known kosher brands among non-Jews. For many years, Hebrew National relied on a body within the company to certify its products kosher. Many Orthodox Jews did not feel that Hebrew National's kosher standards were up to those set in place by groups such as the Orthodox Union, Kof-K, and the like, and as such, would not consume Hebrew National beef-based products.

The Conservative movement also did not regard Hebrew National acceptable and therefore not Kosher. Rabbi Paul Plotkin, the chair of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards' Kashrut Committee, wrote that "Until recently, Hebrew National, which is widely distributed, wasn't 'kosher enough.' Its supervision was unacceptable to many Jews who keep kosher including the Conservative movement."

In the early 2000s, Hebrew National switched to an external certification group, the Triangle K, under the auspices of Rabbi Aryeh Ralbag, which was widely seen as somewhat of an upgrade in its standards of kashrut. In 2004, the Conservative Movement found the upgrade sufficient to be acceptable by Conservative standards. The Rabbis Ralbag and Plotkin conferred jointly and developed a strategy for consistent monitoring of the products labeled kosher by Hebrew National.

By reducing production facilities to just one location, expenses were dramatically reduced for upkeep, utilities, employees, and maintenance. The production process was streamlined so that a viewing station kept an eye on each individual sausage that passed through the facility. Rabbis Plotkin and Ralbag share monitoring duties amongst a group of other Rabbis, allowing for a pure and reliable dedication to the purveyance of Kosher hot dogs. Hebrew National hot dogs are, in this way, able to claim their product as Kosher. In a blog post on the subject, Conservative rabbi and kosher certification entrepreneur Jason Miller lamented the fact that in several baseball stadiums in the United States, Hebrew National hot dogs are publicized as kosher "when in fact they are cooked on the same grill as the non-kosher hot dogs and sausages" and served on dairy hot dog buns.

Nonetheless, The Jewish Daily Forward reported that most Orthodox authorities did not follow this endorsement, and most Orthodox Jews continue not to rely on its kashrut.

In June 2012, ConAgra Foods Inc. was sued by 11 people in Minnesota for falsely advertising their product as kosher. Their complaint rests on the issue of ConAgra unlawfully tricking people into thinking they are buying kosher meat and being able to charge a premium fee for this alleged fallacy.

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...