Categories

Categories

- Home

- Railroad

- Modern Railroads

- Chicago, Rock island, and Pacific Railroad Company 1960's

Chicago, Rock island, and Pacific Railroad Company 1960's

Product Description

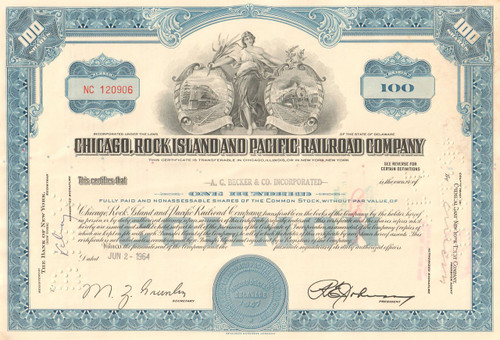

Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad Company stock certificate 1960's

Popular railroad collectible featuring a vignette of a classical female figures flanked by framed train scenes (one diesel, one steam). Issued and cancelled. Dated 1960's.

The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad (CRI&P RR) was a Class I railroad in the United States. It was also known as the Rock Island Line, or, in its final years, The Rock.

Its predecessor, the Rock Island and La Salle Railroad Company, was incorporated in Illinois on February 27, 1847, and an amended charter was approved on February 7, 1851, as the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad. Construction began October 1, 1851, in Chicago, and the first train was operated on October 10, 1852, between Chicago and Joliet. Construction continued on through La Salle, and Rock Island was reached on February 22, 1854, becoming the first railroad to connect Chicago with the Mississippi River. In Iowa, the C&RI's incorporators created (1853) the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad Company (M&M), to run from Davenport to Council Bluffs, and on November 20, 1855, the first train to operate in Iowa steamed from Davenport to Muscatine.

The M&M was acquired by the C&RI on July 9, 1866, to form the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad Company.

In competition with the Santa Fe Chiefs, the Rock Island jointly operated the Golden State Limited with the Southern Pacific Railroad (SP) from 1902–1968. On this route, the Rock Island’s train was marketed as a "low altitude" crossing of the Continental Divide. The Rock Island did not concede to the Santa Fe’s dominance in the Chicago-Los Angeles travel market and re-equipped the train with new streamlined equipment in 1948. At the same time, the "Limited" was dropped from the train’s name and the train was thereafter known as the Golden State. The local run on this line was known as the Imperial.

The Rock Island did not join Amtrak on its formation in 1971, and continued to operate its own passenger trains. The government assessed the "Railpax" entrance fee based upon passenger miles operated in 1970. After concluding that the cost of joining would be greater than operating the two remaining intercity roundtrips, the railroad decided to "perform a public service for the state of Illinois" and continue intercity passenger operations.

The Rock Island also operated an extensive commuter train service in the Chicago area. The primary route ran from LaSalle Street Station to Joliet along the main line, and a spur line, known as the "Suburban Line" to Blue Island. The main line trains supplanted the long-distance services that did not stop at the numerous stations on that route.

When the Milwaukee Road purchased new Budd Company stainless steel bilevel cars in 1961, the Rock Island elected to add to a subsequent order and took delivery of its first bilevel equipment in 1964.

The commuter service was not exempt from the general decline of the Rock Island through the 1970s. Over time, deferred maintenance took its toll on both track and rolling stock. By this time, the Rock Island could not afford to replace the clearly worn-out equipment.

In 1976, the entire Chicago commuter rail system began to receive financial support from the State of Illinois through the Regional Transportation Authority. Operating funds were disbursed to all commuter operators and the Rock Island was to be provided with new equipment to replace the tired 2700 series and Capone cars.

The Rock Island was known as "one railroad too many" in the plains states, basically serving the same territory as the Burlington, only over a longer route. The Midwest rail network had been built in the late 19th century to serve that era's traffic.

The only option for the Rock Island to grow revenues and absorb costs was to merge with another, perhaps more prosperous railroad. Overtures were made from fellow Midwest granger line Chicago and North Western and granger turned transcon Milwaukee Road. Both of these never advanced much beyond the data gathering and initial study phases. In 1964, the Rock Island selected Union Pacific to pursue a merger plan to form one large "super" railroad stretching from Chicago to the West Coast.

After ten years of hearings and tens of thousands of pages of testimony and exhibits produced, now-Administrative Law Judge Nathan Klitenic approved a plan for rail service throughout the west to be covered by four mega-systems: The Chicago-Omaha main would go to the Union Pacific. The Kansas City-Tucumcari Golden State Route would be sold to the Southern Pacific. The Memphis-Amarillo Choctaw Route would be sold to the Santa Fe Railway. The Rio Grande would have an option to purchase the Denver-Kansas City line.

During most of the ensuing merger process, Rock Island operated at a financial loss. In 1965, Rock Island would earn its last profit. With the merger with Union Pacific seemingly so close, the Rock Island cut expenses to conserve cash. In an effort to prop up its future merger mate, UP asked the Rock Island to forsake the Denver gateway in favor of increased interchange at Omaha. Incredibly, the Rock Island refused this and the UP routed more Omaha traffic over the Chicago and North Western.

By the time of the 1974 approval of the merger, Rock Island was no longer the attractive bride it had once been in the 1950s. The Union Pacific viewed the cost to bring the property back to viable operating condition to be prohibitive. The conditions attached to the agreement for both labor and operating concessions were also viewed as excessive. Union Pacific simply walked away from the process, ending the merger case.

Now set free and adrift, both operationally and financially, the Rock Island assessed their options. Rock Island hired a new president and CEO, John W. Ingram, a former Federal Railway Administration (FRA) official. Ingram quickly sought to improve efficiency and sought FRA loans for the rebuild of the line, but finances caught up with the Rock Island all too quickly. With only $300 of cash on hand, on March 17, 1975, Rock Island entered its third bankruptcy.

Creditors, such as Henry Crown, advocated for the shutdown and liquidation of the property. Crown declared that the Rock Island was not capable of operating profitably, much less paying its outstanding debts. At the same time, Crown invested as much as he could in Rock Island bonds and other debt at bankruptcy-induced junk status prices.

Gibbons was released from the Rock Island on June 1, 1984 as the estate of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad expired. All assets had been sold, all debts had been paid, and the former railroad found itself with a large amount of cash. The name of the company was changed to Chicago Pacific Corporation to further distance itself from the defunct railroad and their first purchase was the Hoover appliance company. In 1988, the company would be acquired by the Maytag Corporation.

Ironically, through the mega mergers of the 1990s the Union Pacific railroad ultimately ended up owning and operating more of the Rock Island than it would have acquired in its attempted 1964 merger. The one line it currently does not own is the Chicago to Omaha main line that drove it to merge with the Rock Island in the first place.

Loading... Please wait...

Loading... Please wait...